Giallo, that uniquely Italian strain of horror, exists somewhere between nightmare and art. The name (the Italian word for “yellow”) refers to the color that typically adorned the covers of pulp novels in that country in the 1930s and ’40s. The movement flowered in the 1960s, drawing inspiration from the literary tradition, borrowing its gory plots and lurid colors.

The best giallos fused murder mystery with surrealism, fashion, and eroticism, telling their bloody stories with abundant style. The titles on this list define the genre’s golden era. All of them are stylish, shocking, psychologically perverse, and most importantly, terrifying, basking in the subgenre’s style to deliver emotional and psychologically scarring movies that will scare as much as they’ll seduce.

10

‘Blood and Black Lace’ (1964)

“The killer is a maniac — one who hates beauty, because he cannot have it.” Mario Bava was an influential horror filmmaker, most remembered for the likes of Black Sabbath and Planet of the Vampires. His Blood and Black Lace is arguably the movie that first crystallized giallo‘s aesthetic. The whole thing drips color, decadence, and menace, powered along by a suitably pulpy plot set in a high-fashion house stalked by a faceless killer. Though the plot follows a typical whodunit rhythm,its true brilliance lies in atmosphere, the sense that beauty itself has turned poisonous.

In this regard, Bava’s direction bridged Hitchcock’s suspense and Dario Argento’s delirium, pioneering modern slasher cinema decades before it existed. The imagery is simply fantastic, all crimson walls, cobalt shadows, and mannequins frozen mid-scream, the camera gliding and leering through it all like a voyeur. The themes are surprisingly complex too; beneath the bloody murders, there’s a veiled critique of consumerism, artifice, and obsession.

9

‘The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh’ (1971)

“You can’t run away from what’s inside you.” The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh is something of a deeper cut, but it’s notable within the giallo genre for its psychological complexity. The story revolves around Julie Wardh (Edwige Fenech), a woman trapped in a web of sadomasochistic relationships, blackmail, and murder. It’s part erotic thriller, part feminist nightmare, exploring how pleasure and pain merge under patriarchy’s gaze. The violence feels intimate, almost romantic, turning every kiss into potential betrayal.

Simply put, this movie is incredibly stylish. Sergio Martino’s direction is both sensual and sinister, draping blood in velvet and paranoia in perfume and maintaining a suitably uneasy tone throughout. Once again, there are interesting ideas at play. Beneath its genre trappings, The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh is a study in female trauma and gaslighting that was ahead of its time. Fenech’s performance anchors the madness: vulnerable, alluring, and defiant.

8

‘A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin’ (1971)

“I dreamt I killed her… and when I woke up, it had happened.” A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin is one of the strongest efforts by Lucio Fulci, the genre giant who made The Beyond, The House by the Cemetery, Zombi 2, and other pulpy delights. This one unfolds in swinging London, centering on Carol Hammond (Florinda Bolkan), a socialite whose psychedelic dreams blur into reality after a brutal murder next door. What begins as a mystery evolves into a hallucinatory descent through repression, guilt, and voyeurism.

Fulci serves up a steady stream of striking sights and sounds: surreal montages, haunting soundscapes, and shocking imagery that borders on the avant-garde. The film’s dream sequences, in particular, are filled with dripping colors and floating bodies, anticipating the psychological horror of Black Swan and Mulholland Drive. Yet, alongside the surrealism is a refreshing dose of empathy: Carol’s unraveling mirrors the cost of societal conformity and sexual suppression.

7

‘The Case of the Scorpion’s Tail’ (1971)

“We’re all greedy for something — money, love, or life itself.” Also directed by Sergio Martino, The Case of the Scorpion’s Tail blends classic noir intrigue with Mediterranean glamour. After a plane explosion leaves a widow (Ida Galli) with a fortune (and a target on her back), a chain of murders follows across Greece. The story starts as a typical procedural but quickly becomes an elegant bloodbath. Martino’s gift lies in his pacing: every revelation feels inevitable yet shocking. The visuals deliver, too. The cinematography evokes Hitchcock filtered through heat haze, every sunlit shot concealing danger.

The film’s mixture of jet-set beauty and grotesque violence defined giallo’s international appeal. It’s less overtly surreal than Fulci or Argento, but its craftsmanship and tension make it no less disturbing. The murders are swift, the tone chillingly detached, the moral universe utterly hollow. If you like energetic filmmaking, exotic locales, and gory mayhem, The Case of the Scorpion’s Tail is the giallo for you.

6

‘The House with Laughing Windows’ (1976)

“Beware the painted smile of the saints.” Pupi Avati’s The House with Laughing Windows trades giallo’s usual urban glamour for rural dread, and the result is unforgettable. In it, a young art restorer (Lino Capolicchio) arrives in a decaying village to restore a fresco, only to uncover a legacy of torture and religious mania. Unlike most gialli, Avati avoids flashy style; his horror seeps slowly, organically, from mood and isolation. The film builds unbearable tension through silence, heat, and superstition, building up to one of the most disturbing finales in all of Italian horror.

There are no masked killers or black gloves here, only human depravity hidden behind provincial smiles. The movie’s realism makes it feel cursed, as if we’ve wandered into a community that exists outside morality itself. It’s giallo stripped of glamour, and all the more horrifying for it. All in all, The House with Laughing Windows is proof that atmosphere can wound more deeply than violence.

5

‘Tenebrae’ (1982)

“The impulse had become irresistible. There was no way to stop it.” By the early ’80s, Dario Argento had already revolutionized giallo, and he capped off that achievement with this self-referential masterpiece. Tenebrae (meaning “shadows”) follows an American novelist (Anthony Franciosca) whose violent books inspire a series of murders in Rome. Argento turns this straightforward story into a meta-commentary on art, obsession, and censorship. The director flexes his visual muscles here, too, resulting in countless memorable images.

Indeed, every frame pulses with geometric precision: white walls, red blood, and camera movements that feel supernaturally fluid. The famous crane shot, gliding across an apartment’s exterior, remains one of the genre’s great feats of visual tension. All these strengths add up to a movie that functions as both a return to the giallo roots and a critique of them.It’s slick, cerebral, and shockingly savage, a perfect synthesis of intellect and terror.

4

‘The Bird with the Crystal Plumage’ (1970)

“I saw the murder… but I saw it wrong.” Argento strikes again. The Bird with the Crystal Plumageis the movie that both launched the director’s career and the giallo boom itself. It’s not hard to see why: the film is a near-flawless exercise in tension and visual design. Tony Musante leads the cast as Sam Dalmas, an American writer who witnesses an attempted murder in a Rome art gallery but becomes obsessed with uncovering what he didn’t see. His quest makes for a surprisingly human story about perception and trauma: the idea that memory itself can lie.

As usual, Argento tells the story with exquisite visuals. Here, his use of architecture (glass walls, angular corridors, modernist emptiness) creates a palpable sense of paranoia. Every shadow is art-directed, every scream choreographed like opera. The cherry on top is the eerie score from the great Ennio Morricone, blending lullabies and dissonance, amplifying the film’s hypnotic unease.

3

‘Don’t Torture a Duckling’ (1972)

“Everyone here hides behind a mask of innocence.” Perhaps Lucio Fulci’s most underrated film, Don’t Torture a Duckling is both a gripping mystery and a savage critique of religious hypocrisy. Set in a rural Italian village plagued by child murders, it pits superstition, corruption, and ignorance against reason. At the heart of it all is Florinda Bolkan’s devastating performance as an ostracized woman accused of witchcraft. Through her, Fulci paints a fascinating portrait of small-town Italy, where politics, social pressure, and the church constrain people’s lives.

Fulci’s direction is restrained yet seething with anger. The imagery evokes both realism and nightmare, showing us decaying churches, muddy graves, and broken dolls. The violence, when it comes, is brutal but purposeful, exposing a community rotted by repression. The cumulative effect of all this is less about shock and more about indictment.Don’t Torture a Duckling is a giallo about innocence destroyed by faith, and faith destroyed by fear.

2

‘Suspiria’ (1977)

“You wanted to kill Helena Markos! Death to all that oppose me!” Before Luca Guadagnino‘s wintry remake, Argento wowed audiences with his vibrant original, one of the most visually striking horrors of its time. Suspiria follows an American ballet student (Jessica Harper) who discovers that her prestigious academy is run by witches. What makes it terrifying isn’t plot but rather sensation. In Argento’s skilled hands, color, sound, and movement become weapons.

Goblin’s score screeches like ritual music from another world, while the use of saturated reds, blues, and greens creates an atmosphere that feels simultaneously toxic and divine. Every murder is staged as a grotesque ballet, every corridor a descent into hell. It’s a combustible admixture of aesthetic splendor and visceral fear. The story touches on the loss of control, the collapse of order, and the intrusion of the irrational. In short, Suspiria is giallo at its most operatic, otherworldly, and beautiful.

1

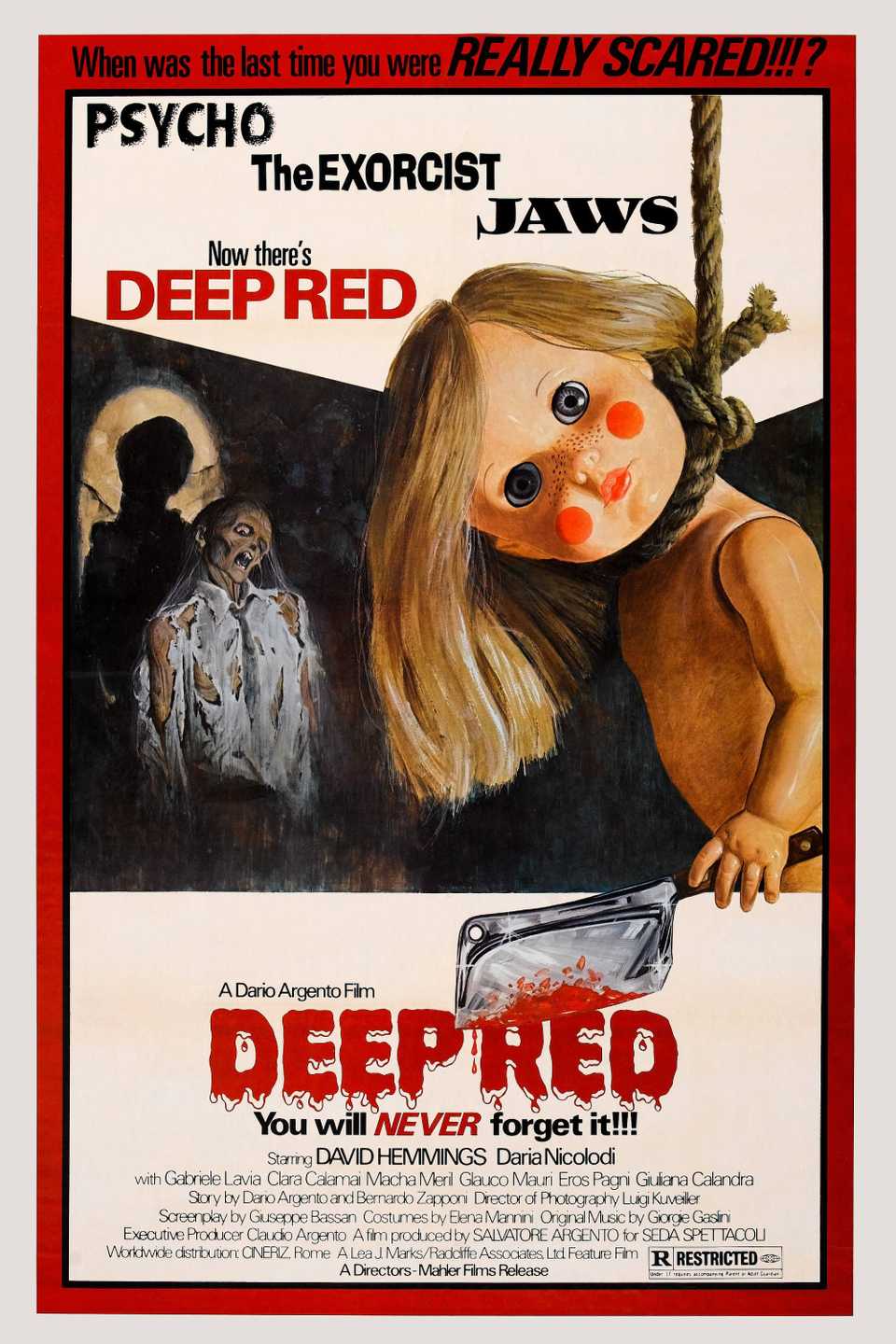

‘Deep Red’ (1975)

“It’s always the same: you think you’ve solved it, and then you find out you’ve just been playing someone else’s game.” If The Bird with the Crystal Plumage invented modern giallo, Deep Red perfected it. Argento’s magnum opus fuses Hitchcockian suspense, expressionist visuals, and rock-operatic sound design into a work of pure nightmare logic. The plot, about a pianist investigating a psychic’s murder, is just scaffolding for Argento’s real art: elaborate camera movements, murders staged as surrealist tableaux, and Goblin’s thunderous score pounding like a heartbeat from hell.

The whole thing is crafted with thought and care. Every detail, from shattered mirrors to childhood drawings, becomes a clue and a metaphor. There’s genuine pathos to the pulp, a meditation on memory, trauma, and the horror of what we forget. All these qualities mean that Deep Red is the pinnacle of giallo, a movie where fear and profundity coexist. Stylish, intelligent, and unnervingly emotional.